Balance of power is one of the oldest and most enduring concepts in a geo-strategic environment preying on mistrust and hegemonic design of powerful and threatening states; it is often the only dependable strategy. It is not surprising, therefore, that since the end of the Cold War, the dynamics of power balancing have devolved at the regional level as the global picture is still amoebic and amorphous. Great powers like Russia and China have taken tentative steps towards counterbalancing by developing coalitions like SCO and BRICS to guard against U.S. predominance and are likely to contest USA in skirmishes in regional context to flex muscle and gauge thresholds of the opponent. China is pursuing an indirect form of balancing through regional mobilization and economic hegemony but may not be in a position to build a true anti-U.S. coalition or counter balance USA on its own steam[1]. But the logic and stability of this new situation remain unclear. Balance of power today is hybrid in nature a heady cocktail of political, economic and military aspects that shapes nation states’ balancing approach against the adversary in a system. Therefore, to maintain the equilibrium and to thwart any military aggression, threatened states are compelled to develop “strategic alignment” for regional balancing.

In context of South Asia, the balance of power equation has become enormously complex as it primarily rests on the interplay between India and Pakistan; two nuclear armed states. India and Pakistan rivalry has stakes direct or indirect for three other extra-regional nations i.e. China, Russia and USA. Revocation of Article 370 by the political dispensation in New Delhi has further hardened and calcified positions leaving minimalistic leeway for realignment and negotiations with Pakistan adopting a flagrant stance. It has left no stone unturned to up the ante on the issue by making efforts to galvanize international opinion against India.

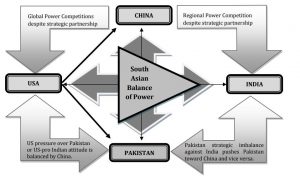

Global Powers in the sub-continent politics have always been an unbalancing factor for the regional power equilibrium. The global players encourage and coaxed is engagement and dissonance among the rivals to maintain their global suzerainty by engaging in strategic partnerships with regional players by influencing their foreign policy and strategic articulation. Recent utterances by President Trump on mediation in Kashmir and then the usual backtrack has further queered the pitch; China too is not helping the cause by their blatant inflections on an internal policy decision of India. USA, China, India and Pakistan align to make a strategic quadilateral, whereas Pakistan and China angles against a common rival that is India, while US has aligned with India as a strategic partner and aspires to assign it with an active role in US engagement with China. USA has also started to engage China in direct confrontation with Trade Wars which may have ramifications in the region. This re-calibration of relations between USA and Pakistan as well as China has deepened the levels of congruence between China and Pakistan and automatically deepened the dissonance between China and India.

Relations of China and Pakistan have influenced the South Asian politics and against all odds, have achieved continued to gain traction. In contrast, the Indo-US strategic alignment is a counterbalance of power equation of the regional politics that manifest mainly bilateral strategic partnerships based on “engagement and resistance”. Pak-China strategic partnership has endured due to rentier status of Pakistan encumbered by a fragile economy heavily dependent on Chinese largesse while Indo-US strategic alignment has points of dissonance; India’s procurement of Russian military hardware, relations with Iran and persistence of strategic autonomy by India adequately displayed by the very public refusal of Trump’s offer on mediation. Despite the disagreements; Indo-US nuclear deal, QUAD alignment with Australia and Japan is in the Chinese view to keep an eye on it as well as prey on Pakistan’s perennial fear of Extra Regional Force (ERF) intervention to deny it usage of nuclear facilities could play with the delicate balance of power in the subcontinent. Therefore, the strategic quadrangle of China-Pakistan, India-United States is getting intense and influencing the region.

South Asian balance-of-power, a new dynamic of balance-of-power namely “Strategic Quadrangle” has emerged. This quad has the propensity of collapsing into a line, with United States and India gravitating towards one end and China and Pakistan towards the other, leaving these two sets of players diametrically opposed”[2].

Strategic Quadilateral Of South Asia[3]

China and Pakistan are making strong partnership against Indo-U.S. strategic alliance and seeking newer partners and re-balancing erstwhile equations. In the larger context of the region with Iran, Saudi Arabia and Russia also being drawn into the quagmire which presently represents a larger South Asia with Afghanistan also becoming a bone of contention. Pakistan has been trying to offset India’s attempt of diplomatic isolation through external balancing in terms of gaining qualitatively superior weaponry and diplomatic support from Turkey, Russia and China. Pakistan’s grip on their perennial stronghold in Middle East has slackened despite the OIC statement post revocation of Article 370, Pakistan’s diplomatic onslaught has not met with the traction Pakistan was expecting and has led to dismay and frustration in the political dispensation, further salt on the wound was added by Bahrain bestowing on Prime Minister Narendra Modi the country’s top civilian honor, the ‘Order of Zayed’.

Meanwhile economically US has forced China into a trade war to strangle her economy[4] and imposed checks on military exports to Pakistan[5], this is to say that Pakistan’s military capability and China’s economy’ the invisible actors which caused strategic imbalance in South Asia are no more a force to reckon with. Besides in the context of China, U.S. is attempting to develop and cultivate alliance partners around China’s periphery primarily in the form of its military presence in Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia, Afghanistan, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea. Both U.S. and India consider China as a major challenge and are aligning themselves to counter the Chinese hegemony in the region and globally, with India picking up the cudgels at the regional level while the USA manages the global competition.

However, there is an aspiration versus capability mismatch conundrum for India, on a standalone basis the regional tug of war of power and influence between the two Asian giants has rarely been so stark, especially in India’s backyard. Earlier this year, the Maldives—once closely tied to India—theatrically shifted allegiance to China and to an authoritarian political model that isolated the country’s India-friendly democrats. However, India found political levers in Male to retrieve the situation after the elections have propelled a pro India dispensation to power. Similar tug of war ensues in Nepal and Myanmar; Indian policymakers are faced with a dilemma. On one hand, they have a smaller purse with which to challenge China. But, if they step back, they are surrendering to a familiar Chinese strategy: a multi-layered effort to force other regional powers to abandon their spheres of influence. India’s neighbours have long been targets for China’s affections.

For India’s partners across the world, the current government’s pursuit of a “reset” with China post Wuhan is an indicator of the regional compulsions on India. Indian policymakers meanwhile must pragmatically evaluate the benefits and costs of placating China. Have similar efforts in the past by Japan or the US paid off? If not, is there another option? Many would argue there is. India has long cherished what it calls its “strategic autonomy,” seeking to maintain a Jeffersonian distance from “entangling alliances.” Yet that lofty disregard of global rivalries is unaffordable when a hegemon can so easily pick off your neighbours one by one.

Rather than seeking to appease China, India’s interests would be better served seeking to repair and strengthen its relationships—economic and political—with democracies in Asia and with nations that share its interests and values irrespective of their political orientation. Sri Lanka was compelled to transfer the Chinese-built strategic port of Hambantota to China on a 99-year, colonial-style lease, because it could longer afford its debt payments. Sri Lanka’s experience was a wake-up call for other countries with outsize debts to China. Fearing that they, too, could lose strategic assets, they are now attempting to scrap, scale back, or renegotiate their deals. On a recent official visit to China, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad was overtly critical of China’s difficult-to-repay loans and entrapment of smaller countries. Mahathir’s stand reflects a push back against China’s investment, and lending practices and presents an opportunity for India to re-calibrate its choices[6].

. Countries as diverse as Bangladesh, Hungary, and Tanzania have also canceled or scaled back BRI projects. Myanmar, hoping to secure needed infrastructure without becoming caught up in a Chinese debt trap, has used the threat of cancellation to negotiate a reduction in the cost of its planned Kyaukpyu port from $7.3 billion to $1.3 billion[7].Even China’s closest partners are now wary of the BRI. In Pakistan, which has long worked with China to contain India and is the largest recipient of BRI financing, the new government has sought to review or renegotiate projects in response to a worsening debt crisis with a two billion USD drawdown on the railway project to upgrade Main Line-1 as part of Eastern alignment of CPEC.

President Trump’s trade war with China is grabbing headlines, but Trump is far from alone in criticizing China. Hong Kong has turned into a festering wound for China which refuses to heal and is likely to bring back memories of June 1989 Tiananmen Square incident. Hong Kong may not go down without a fight and is likely to find more external support and more so from USA where politicians have renewed calls to pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act[8].The bipartisan legislation would require the White House to carry out an annual review to determine whether Hong Kong’s special trade status, which allows it to be recognized as a separate customs territory to mainland China, can still be justified. G7 leaders meeting in France on 26 August 19 backed Hong Kong’s autonomy as laid out in a 1984 agreement between Britain and China and called for calm in the protest-hit city.[9] China was prompt to red flag the statement as meddling in internal affairs of China. Hong Kong has in effect given India a perfect alibi for Kashmir. All factors taken into account, as the saying goes, the pot cannot call the kettle black. India did not comment and has scrupulously maintained silence on the developments in Hong Kong but the precarious Chinese position with respect to their stance on Article 370 has not been lost to anyone in the geo-political intelligentsia. The fact is that China has grown strong and rich by flouting international trade rules; a number of countries are recalibrating economic ties and imposing anti-dumping or punitive duties on Chinese goods. Many in India have questioned the relevance of non-alignment after the collapse of bipolarity. At the rhetorical level, New Delhi appears reluctant to discard its commitment to non-alignment. At a popular level, there is a strong view that India has moved away from its nehruvian ideology and replace it with hyper-realism[10] with emphasis on genuine multilateralism, and the promotion of global collective security.

India’s formal emphasis on non-alignment should not, however, obfuscate the reality of a determined bid by India in the recent years to transform its bilateral relationships with all the major power centres of the world. Possibility of a formal Indian alliance with the United States aimed against China is unrealistic but India may be a realist in choosing sides in the new Economic Cold War between the United States and China and developing counterbalances scaffolded on its perennial friendship with Russia. Such an external orientation will be rooted in two basic propositions. First, India needs an intensification of cooperation with all the great powers; global or regional, without being tied down. Second, the expansion of India’s role in the world is likely to be achieved less by external political alliances and more by the rapid enhancement of its internal and external economic capabilities. For this reason, New Delhi must begin to define its foreign policy goals aligned with national security including economic security in a modest and pragmatic manner. India’s experiment with the politics of balance of power in a complex world must look beyond South Asia to engage peripheral regions like West Asia, Central Asia and SE Asia and as a large nation, committed to an independent judgment on various issues; India may have to play a sublime partner in any alliance system to counter China. India must continue to move further towards a realistic policy framework[11]sans its past emphases on ideology and political first principles.

References

[1]https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/can-china-build-an-anti-us-alliance/2018/07/05/2e707e82-808c-11e8-bb6b-c1cb691f1402_story.html accessed on 18 Sep 19

[2]Markey, Dan, Paul Haenle, and Lora Saalman. “Partners in Peril: U.S.-India-China-Pakistan.” Report of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. April 12, 2011. Accessed 06 Oct 18. http://www.carnegieendowment.org/2011/04/1 2/partners-in-peril/9s.

[3] ibid

[4]Maj Gen PK Mallick,VSM (retd) US-CHINA Trade War: Analyses of Deeper Nuances and Wider Implications https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/US-CHINA-Trade-War.pdf accessed on 19 Sep 19

[5]ShubhangiPandey, US sanctions on Pakistan and their failure as strategic deterrent

https://www.orfonline.org/research/42912-u-s-sanctions-on-pakistan-and-their-failure-as-strategic-deterrent/ accessed on 15 Sep 19

[6]Hannah Beech, We Cannot Afford This’: Malaysia Pushes Back Against China’s Vision;https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/20/world/asia/china-malaysia.html accessed on 17 Sep 19.

[7]https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2158015/myanmar-scales-back-china-funded-kyauk-pyu-port-project accessed on 19 Sep 19

[8]https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3289 accessed on 01 Sep 19.

[9]https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/g7-leaders-back-hong-kong-autonomy-call-for-calm-11844232 accessed on 27 August 19.

[10]KantiBajpai; https://globalbrief.ca/2013/03/india-does-go-grand-strategy/ accessed on 11 Oct 19.

[11]https://www.orfonline.org/research/case-classically-conservative-foreign-policy-based-realism/ accessed on 11 Oct 19.