Bashir Assad is a writer and journalist based in Srinagar. He primarily writes about Kashmir, national security, and the various dynamics of the ongoing conflict. He has contributed immensely to the over-flowing discourse on the Kashmir conflict. Interestingly, even though the subject has been thoroughly saturated, his works provide a refreshed and personal understanding of the topic. This is simply because his arguments are guided, in part, by lived experiences and perfected by his journalistic lens. He spent a considerable amount of his youth preaching Maududi ideology that today faces his scrutiny. He was deeply enmeshed in the ideologies that he now highlights as the religious agents that share the blame for radicalizing Kashmiri youth. His deep understanding of the narratives spun by these religious agents and their impact on the psyche of the youth can be credited to the fact that he was a member of the indoctrinated youth he discusses today. How this ‘religiosity’ gradually made way for militancy is what broke the spell for him. Works on Kashmir either speak from an external understanding or an internal voice. Assad’s voice is distinct as it does not operate on any prominent biases and is equally critical of both the Indian state, the transformed Kashmiri society, and the political benefactors that have mushroomed here. His words represent those who understand the imperfections of the Kashmiri society but lack the courage to speak up. There is no doubt that his candid criticism has received backlash in very extreme forms. Despite that, his work seems to be driven by heartache due to the demise of the once tolerant, generous, and welcoming Kashmir whose streets, today, are solely an abode to hate and gore of radicalized Islam.

Bashir Assad is a writer and journalist based in Srinagar. He primarily writes about Kashmir, national security, and the various dynamics of the ongoing conflict. He has contributed immensely to the over-flowing discourse on the Kashmir conflict. Interestingly, even though the subject has been thoroughly saturated, his works provide a refreshed and personal understanding of the topic. This is simply because his arguments are guided, in part, by lived experiences and perfected by his journalistic lens. He spent a considerable amount of his youth preaching Maududi ideology that today faces his scrutiny. He was deeply enmeshed in the ideologies that he now highlights as the religious agents that share the blame for radicalizing Kashmiri youth. His deep understanding of the narratives spun by these religious agents and their impact on the psyche of the youth can be credited to the fact that he was a member of the indoctrinated youth he discusses today. How this ‘religiosity’ gradually made way for militancy is what broke the spell for him. Works on Kashmir either speak from an external understanding or an internal voice. Assad’s voice is distinct as it does not operate on any prominent biases and is equally critical of both the Indian state, the transformed Kashmiri society, and the political benefactors that have mushroomed here. His words represent those who understand the imperfections of the Kashmiri society but lack the courage to speak up. There is no doubt that his candid criticism has received backlash in very extreme forms. Despite that, his work seems to be driven by heartache due to the demise of the once tolerant, generous, and welcoming Kashmir whose streets, today, are solely an abode to hate and gore of radicalized Islam.

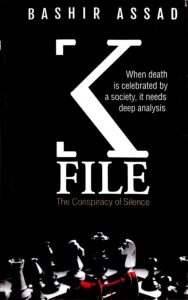

Bashir Assad’s K-File is a key to the Kashmir conflict for the layman. Although, an English dictionary, a suitable key to the ornamental and allegorical language in this text, is highly recommended. Among the plethora of texts on the Kashmir conflict, where space for another is unimaginable, Assad introduces a fresh and fairly unique narrative to an issue so drained. Ordinarily, authors and scholars would summon to trial either the center or Pakistan as the main defendant. While the Pakistani propaganda should be held responsible for provocation, and the Pakistani state for adding fuel to the fire by redirecting the extremist Islamic ideology and Jihad introduced in Afghanistan as a weapon during the Cold War to Kashmiri society, they cannot alone take all the credit. Assad takes a different route altogether, analyzing how the internal dynamics of Kashmiri society have kept the fire burning.

It is indeed a brave book that breaks the unwritten pact among Kashmiris to not expose ‘the conspiracy of silence.’ Reading this work is similar to looking through a microscope as it enlarges the conflict’s most minute dynamics that are invisible to the naked eye. Assad’s work highlights the actors that have helped Kashmir transform into a communalistic society. He bestows the blame on distorted narratives–a response to political conflicts–that eventually became deeply Islamicized with the help of Pakistan sponsored terrorism. With militancy in the picture, these Islamists completely changed the demography of the valley; intolerance and exclusivity became the new norm.

He claims the current violence to be running on false narratives and an illusion of oppression. There is no doubt that Kashmir has been wronged politically by several political entities. From undermining the state’s democratic institutions through rigged elections till 1987, the institutionalization of corruption at the hands of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed–a Prime Minister installed in Sheikh Abdullah’s place, and an overall “erosion of autonomy,” the polity is far from innocent in this case. However, these feelings of social exclusion and alienation largely only result in violent yet individual responses to injustice, as claimed by Assad. The illusion of being the sole state whose rights have been clipped and whose streets witness the heavy military presence has shaped the way Kashmiris retort. Instead of finding better ways to communicate grievances, like most people in other parts of the world, these illusions and narratives made sure that Kashmiris perceive violence as the only avenue. Why is it that Kashmiri Pandit youth that lost their homes due to extremist violence did not take up arms in a similar fashion? The large-scale violence and transformation of Kashmiri society from benevolent to intolerant warrant a deeper look into the various agents thriving here.

The conflict in Kashmir ceased to be political with the culmination of former Chief Minister Sheikh Abdullah’s tenure. Since then, the political conflict has metamorphosed into a divisive and gory war where heinous murders of local youths by the militancy are a reaffirmation of the Muslim identity. Assad boils down the current phase of violence to the Mosque, Mullah, and Militant. This catchy alliteration can be expanded to understand the casteist and power-hungry Mullah caste propagating extremist propaganda, through the various schools of Islamic thought, onto the impressionable and unemployed youth of lower castes. The Mullah castes have ensured unemployment for the lower castes and pushed the underprivileged youth onto the frontlines of a war that secures their own interests. It is ironic how the actors urging the lower caste Kashmiri youth to fight for their democratic rights are themselves authoritarian in nature, running on fascist principles. These are the same elites that benefitted from the Maharaja Hari Singh’s autocratic rule and his feudalistic policies. Thus, they were inherently opposed to Sheikh Abdullah who represented the masses and his land reform policies. Moreover, since he supported Kashmir’s accession into India, Mullahs began spinning grievances in that context to create an opposition to his work.

It is crucial to examine the background of the militant to understand why the illusions and narratives perpetuated here are ingested with ease. Most of these militants lead lives plagued with uneducation and poverty. Education in the valley has suffered immensely from the absence of Kashmiri Pandits. When Hindus and Muslims lived harmoniously in Kashmir, the only form of competition was positive in nature and in terms of education. After the exodus, this same competition was concentrated between different schools of the Sunni sect of Islam itself. Today, Kashmir finds each and every religious organization with a militant backing. What was once a political conflict is now a divisive war supported by radical Islam spread by Jamaat-e-Islami in the 1970s. The Wahabis and Deobandis carry this baton further and share responsibility for the current wave of propaganda and violence. It is no longer about the democratic rights of Kashmiris but a war with Muslims on one side and their perceived oppressors on the other. Assad highlights how popular figures such as Syed Ali Geelani have perpetuated ideologies that celebrate barbarianism with a distorted view of human beings. The Maududi ideology finds these killings to be an act of asserting the Muslim supremacy. Kashmiri youth find liberation in killing innocents and Assad wishes to present the cause of this deeply problematic reality.

This monstrous ideology can be linked to the Salafi school of Islam that largely propagates teachings of the Jamaat. It presents a sharp contrast to Sufism that earlier defined the lives of Kashmiri Muslims. Assad further questions how this tolerant and inclusive school of Islam was so quickly replaced by an intolerant ideology. The simple reason is that Sufism was apolitical in nature and focused on emancipation and spirituality. Its teaching did not provide answers to the political unrest in the post-1947 Kashmir. This void allowed the primitive ideologies of the Jamaat to settle in and brainwash impressionable youth. The Indian state allowed it to become an organization and run schools that drew people because their schools had better facilities. In these schools, ideas of Islamic rule, Caliphates, and Kafirs being unworthy of governing Muslims were fed to young students. Interestingly, the Jamaat was composed of Mullahs–Geelanis, Sheikh, Handanis, Naqshbandis, Andrabis, Bukharis–who not only introduced toxic Jihad but established the supremacy of Mullahs. The extremist ideologies taught in these schools easily spread to other education institutes as well. They were able to intrude by the hand of the indoctrinated product of Jamaat schools that found themselves in government offices. Moreover, once the Jamaat-e-Islami and its Fallah-e-Aam trust–the educational wing–was banned for glorifying anti-social practices, their teachers were absorbed in other schools, furthering the Jaamat’s agenda. Thus, impressionable youth (ages 12-20) fell prey to either a teacher whose sole focus was to propagate Jamaat ideology or one who was more concerned with teaching their version of Islam. Ironically, their children and those of elitist Mullahs will not be found in such schools. Moreover, except for the Red Mullah Clan (Shahs) who constitute the leadership of some terrorist outfits, Mullahs and their families have not been physical participants of Jihad and militancy. The age of the Internet makes the propaganda machine even more efficient and the one odd case of human rights abuse further instills the sense of victimhood. While the Mullahs are small in number, they have maintained their dominance and privilege by occupying the majority of the government offices and jobs in both the private and public sectors, leaving the lower caste free to become pawns in a war they helped create.

Assad also presents an interesting stand on the concept of ‘civilian death’. It is commonplace for youth, who inhale extremist propaganda like an opiate, to confront security forces in the midst of an operation. Assad highlights that the Mullahs, that drive them to Jihad, do not discourage them from risking their life like this. He questions whether a youth like this who is intervening with the obvious motive of allowing the militants a chance to escape can be called a civilian. Interestingly, when this accomplice gets hit by a stray bullet, this ‘civilian death’ is further used to malign the already toxic sentiments against the security forces. Such is the inhumanity of the murderous Mullah elites. The people who have been the root cause of incomputable innocent death become the finest Human Rights activists once one of their pawns becomes a casualty. They do not have any love lost for these dispensable foot-soldiers; their death becomes another weapon to radicalize. One is either a Muslim or an infidel, a supporter or hands in glove with the oppressor. There is no space for dissent in today’s Kashmir. The dissenter faces the black void of death sooner than scheduled. The martyrdom of these young men is celebrated by their parents for a while, but it only leads to broken parents and desolate households once the celebration of these small ‘victories’ dies down.

Assad calls the Kashmiri politicians and media double dealers. While so-called Indian agents are eliminated, ISI agents are celebrated. However, these separatists Mullahs in the Hurriyat Conference were in touch with Indian since 1989 and simultaneously in cahoots with the ISI. However, their collusion with the ISI has proved to, ironically, be beneficial to the Indian state. This political conflict is now globally acknowledged as Pakistan sponsored Islamic terrorism rather than a domestic matter. He calls the media and press double dealers as they negotiate for funds from both India and Pakistan to aid the survival of their publications. Yet, the content published in these publications operates not on journalistic ethics but obvious biases. It is simply a source of instigation and a venture to further push Kashmiri society into the ghastly Jihad mill.

These are only a few of the many prominent narratives that have faced his scrutiny in this text. Any summary of this highly educative and informative work would be a hugely deficient account. The author does not write with any political alliances or biases. The book seems to be coming from the simple desire to educate and educate with the truth. The author does not spare any agent in his investigation. It is impossible to not leave a copy of this text plastered with margin notes and post-its, it is that engaging. This is not a passive intake of information. As it scrutinizes narratives and history itself, it compels the reader to further extend that scrutiny to narratives they have absorbed as the gospel truth. Not only is this book brave in finding its feet without the crutch of a political alliance, but so is its author for undertaking a project that comes with a looming risk of being attributed to various labels that could malign his image and threaten his life.