Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, launched in 2012, represents not merely an effort to combat graft but the Communist Party’s longest-running mass campaign in its century-long history. What began as a promise to hunt both “tigers and flies” has evolved into an enduring instrument of political control that reveals the fundamental contradictions and systemic failures of authoritarian governance in China.

The Historical Context: An Unprecedented Campaign

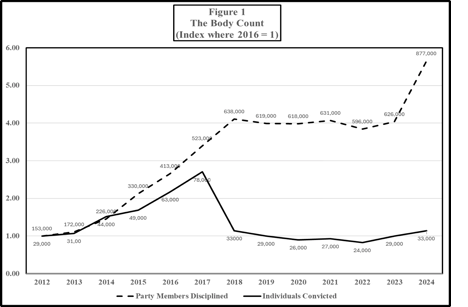

The scope and duration of Xi’s anti-corruption drive distinguishes it from all previous CCP mass campaigns. Unlike Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) or the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), Xi’s campaign has persisted for over 12 years without any indication of ending. This sustained effort has investigated over 6.2 million party members, convicted 466,000 individuals on corruption charges, and detained 417 senior officials and 126 senior military officers as of 2024.

Source: China Research Center

Recent data from 2024 shows the campaign’s intensity remains undiminished. A record 56 high-ranking “tigers” were investigated in 2024 alone, representing a 25% increase from 2023. The first half of 2025 saw authorities handle 1.21 million leads and file 521,000 cases for investigation, up 28% from the previous year. This escalation demonstrates that rather than achieving victory, Xi’s war on corruption has become a permanent feature of his governance model.

Corruption as a Tool of Power Consolidation

The campaign’s true purpose extends beyond fighting graft, it serves as Xi’s primary mechanism for political control and power consolidation. The anti-corruption drive “resembles a party-building campaign for amassing political power amidst China’s fragmented power structure rather than a systemic remedy to cure endemic corruption”.

Xi has strategically used corruption charges to eliminate political rivals and consolidate authority. The campaign targeted prominent figures including former Politburo Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang, Chongqing Party Secretary Bo Xilai, and numerous military leaders who posed potential challenges to Xi’s authority. By 2024, Xi had purged even his own appointees, with the suspension of Admiral Miao Hua marking the third consecutive defence minister to face corruption charges.

Endemic Corruption at Central and Provincial Levels

Despite over a decade of intensive campaigning, corruption remains deeply entrenched throughout China’s political system. The persistence of graft at the highest levels exposes the campaign’s fundamental failure to address systemic causes. In 2024, 12 of the 56 detained officials held roles in central Party and state agencies, double the number from 2023. This indicates corruption within the Party’s core apparatus, not merely peripheral elements.

At the provincial level, corruption networks continue to flourish despite intensified scrutiny. The campaign has revealed that among provincial officials investigated, more than 80% carried out corrupt activities even after Xi launched his drive. This suggests that rather than deterring corruption, the campaign may have simply driven it underground or made it more sophisticated.

Grassroots corruption accounts for 70% of all punishments, with 48,000 current or former village Party branch secretaries and village committee directors under investigation in the first half of 2025 alone. This widespread base-level corruption undermines the Party’s legitimacy and effectiveness in policy implementation, creating a fundamental challenge to governance.

The Paradox of Authoritarian Anti-Corruption

Xi’s approach embodies the central paradox of authoritarian anti-corruption efforts: the same system that enables corruption is tasked with eliminating it. The campaign relies heavily on opaque Party disciplinary mechanisms rather than legal institutions, concentrating power in Xi’s hands rather than establishing genuine checks and balances. This approach may actually reinforce the authoritarian system that generates corruption in the first place.

The expansion of liuzhi detention centers—facilities that operate outside judicial oversight—exemplifies this authoritarian approach. These centers allow the National Supervision Commission to detain suspects for months without formal charges or legal representation, creating a system that prioritizes political control over due process.

Why Corruption Persists After 12 Years

Several structural factors explain why Xi’s campaign has failed to eliminate corruption despite its unprecedented scale and intensity:

Systemic Institutional Flaws: The absence of clearly defined rules and regulations creates opportunities for corruption throughout the policy implementation process. Local governments exploit regulatory ambiguities to engage in rent-seeking activities while maintaining plausible legal cover.

Centralized Authority Without Accountability: The concentration of power in Xi’s hands, combined with limited independent oversight, creates conditions that foster rather than prevent corruption. Higher-ranking officials with greater access to state assets benefit most from corrupt practices, earning four to six times their official salaries through illicit means.

Political Loyalty Over Institutional Reform: The campaign prioritizes personal loyalty to Xi over genuine institutional reform. This emphasis on political discipline rather than systemic change ensures that corruption adapts to new constraints rather than being eliminated.

Perverse Incentives: The campaign’s political nature creates incentives for officials to demonstrate loyalty through aggressive anti-corruption performance, sometimes leading to fabricated cases while allowing well-connected corrupt officials to escape scrutiny.

Conclusion

Xi’s anti-corruption campaign reveals the instrumentalization of anti-graft efforts for political ends. It demonstrates how authoritarian leaders can use the fight against corruption to consolidate power while the underlying conditions that generate corruption remain unchanged.

The campaign’s perpetual nature suggests that Xi views it not as a temporary measure to clean up the system, but as a permanent tool for maintaining control. This represents a departure from traditional CCP governance, where campaigns typically had defined endpoints. Instead, Xi has created an institutionalized system of political purges disguised as anti-corruption enforcement.

As China enters Xi’s third decade of rule, the persistence and intensification of corruption investigations paradoxically demonstrate both the reach of his power and its fundamental limitations. While he can eliminate individual corrupt officials, he cannot eliminate the systemic conditions that generate corruption without dismantling the very authoritarian structure that keeps him in power. This fundamental contradiction ensures that Xi’s anti-corruption campaign will continue indefinitely, not because it succeeds, but because it cannot succeed without transforming the system it aims to preserve.

The campaign thus stands as the longest political tool in CCP history precisely because it serves multiple functions beyond its stated purpose: eliminating rivals, demonstrating power, maintaining public legitimacy, and providing justification for increasingly authoritarian governance. In this light, Xi’s war on corruption reveals itself as less about cleaning up the system and more about controlling it, a distinction that explains both its unprecedented duration and its ultimate futility.