Chinese Premier Li Qiang presented his second ‘Government Work Report’ on 5 March 2025 at the annual ‘The Two Sessions’ (Lianghui). The annual work report is important for two reasons; first the report provides an overview of China’s economy in the preceding year and second it outlines the government’s priorities for the next fiscal year. Additionally, the report also provides valuable insights into China’s political landscape and the general direction of the country’s policymaking. While the report can be seen as a collation of government’s achievement over the past year, it’s the things the report omits or overlooks that provide real insights into the government’s works and the general direction of China’s economy. This article analyses key indicators of the last three work reports and finds out that, indicators such as GDP growth, urban employment, per capita disposable income, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), grain output, high-tech manufacturing, and new-energy vehicle production, among others, have been selectively highlighted or obfuscated, suggesting a pattern indicative of deeper structural challenges.

GDP Growth: Plateauing Economy

The Chinese economy’s GDP growth trajectory from 2022 to 2024 reflects notable fluctuations. Growth was reported at 3% in 2022, rebounding to 5.2% in 2023, and slightly dipping to 5% in 2024. The modest deceleration from 2023 to 2024 hints at an underlying plateauing effect. Considering the government targeted around 5% consistently in these years, achieving slightly above or near this target masks China’s struggle to sustain historically high growth rates. A comparative analysis of China’s recent economic slowdown with Japan’s economic trajectory in the 1980s and 1990s provides further context. Japan experienced rapid economic expansion in the 1980s, reaching peak annual GDP growth of approximately 6% in the late 1980s. However, from the early 1990s onwards, Japan faced a pronounced slowdown, often described as a ‘lost decade,’ characterized by minimal growth, structural stagnation, deflationary pressures, and sustained economic malaise.

Similarly, China saw unprecedented GDP growth averaging around 9-10% annually from 2000 to 2010, driven primarily by export-led growth, massive infrastructural projects, and significant foreign investment inflows. Post-2010, however, China’s GDP growth gradually slowed, reflecting a maturing economy facing structural bottlenecks, rising debt burdens, demographic challenges, and diminishing returns from traditional growth drivers.

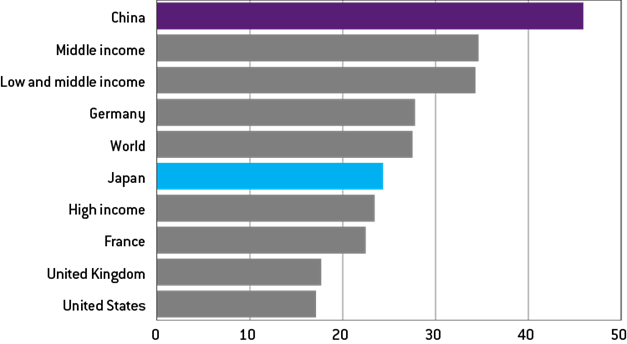

The comparison highlights important parallels: both nations experienced high growth followed by notable deceleration as they transitioned from rapid expansion to economic maturity. China’s recent plateauing suggests it might be entering a similar phase of prolonged moderate growth akin to Japan’s earlier experience. When Japan’s economy faced a significant reduction in investments, it successfully transitioned to a consumption based economy. However, China’s GDP growth stagnation has been followed by low internal consumption paired with high savings ratio. As of early 2020s, China’s savings rate had surpassed 40%, which were highest in the world surpassing even low and middle income economies. If these trends continues China’s economy will not just plateau, it will decelerate.

Figure 1: Savings Rates (%) in the early 2020s, major economies

Source: Natixis, CEIC

Urban Employment and Unemployment Rate

Urban employment data presented a superficially stable picture with new urban jobs gradually increasing from 12.06 million in 2022 to 12.56 million in 2024, accompanied by a declining unemployment rate from 5.5% to 5.1%. However, given China’s demographic shifts, particularly an aging population and a shrinking workforce, these figures merit deeper scrutiny. The minor improvements conceal persistent issues, including youth unemployment, which reached historical highs of over 20% in some urban areas in mid-2023 and 15.7% (after adjustment of methodology) in December 2024 but were notably absent in the 2024 report. By selectively reporting aggregate employment data and excluding sensitive sub-indicators, the government has strategically masks real economic stress.

Per Capita Disposable Income: A Waning Momentum

Per capita disposable income growth showed a marked decline from 6.1% in 2023 to 5.1% in 2024. This decline is particularly revealing because disposable income directly impacts domestic consumption, a vital component of China’s economic model transition towards a consumption-driven economy under the dual-circulation framework. A decrease in disposable income growth signals reduced consumer confidence, tighter household budgets, and potential stagnation in domestic consumption.

The reduced reporting transparency in 2024 compared to previous years underscores official caution, avoiding drawing attention to potential reductions in household economic well-being and purchasing power. The government’s decision not to highlight detailed breakdowns of income sources further points towards sensitivities concerning economic disparities and consumer sentiment.

Consumer Price Index: Stagnation Concerns

The CPI’s minimal growth of just 0.2% in both 2023 and 2024 compared to 2% in 2022 indicates potential deflationary pressures or, at best, stagnant demand conditions in the domestic market. Persistently low CPI growth raises red flags about weak internal demand, posing substantial risks for future economic stability. China’s emphasis on maintaining economic stability and avoiding deflation risks indicates implicit acknowledgment of fragile domestic market conditions, yet this issue remains largely understated in the official reports.

Grain Output: Consistent Yet Challenging

Grain output has steadily risen from 685 million metric tons in 2022 to 700 million metric tons in 2024, reflecting China’s continuous focus on food security. However, the incremental annual increases suggest challenges in significantly boosting agricultural productivity. These moderate gains likely mask difficulties related to shrinking arable land, rural labor shortages, and environmental pressures, which have not been transparently acknowledged in the official discourse.

High-Tech Manufacturing and Tech Transactions: Shifting Emphasis

In 2024, high-tech manufacturing growth stood at 8.9%, and the value of contracted technology transactions increased by 11.2%. Yet, the government’s selective reporting by excluding certain comparative figures, such as the volume of contracted tech transactions from earlier reports, suggests potential stagnation or even decline in certain high-tech segments. By presenting positive yet incomplete figures, China strategically redirects attention towards perceived technological advancement, obscuring areas where progress may be lagging.

New-Energy Vehicles (NEVs): Statistical Manipulation

One of the most telling indicators of selective statistical presentation is China’s reporting on new-energy vehicles. In 2022, the report emphasized an impressive growth rate of 93.4%. However, by 2024, the report only cites the absolute number, 13 million units produced, without a growth percentage. Similarly, the 2023 report completely omitted any statistics on new-energy vehicles production or consumption. This omission strongly suggests significantly slower growth or stagnation. A shift from highlighting growth percentages to absolute figures aligns with efforts to downplay weakening market dynamics or production bottlenecks, potentially related to subsidy reductions, market saturation, and intensifying international competition in EV technology.

Conclusion

China’s annual Government Work Reports from 2022 to 2024 present an interesting combination of highlighted successes and deliberate omissions. The subtle shifts in the way achievements are presented, and the selective disclosure of certain facts reveal significant structural challenges within China’s economy. They selective reporting also reveal the neo-Maoist leadership of Xi Jinping as it mirrors the false reporting of agricultural and industrial output during the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) campaign unleashed by Mao. By carefully analysing both what is explicitly mentioned and what remains unsaid, we can understand that while China’s economy continues to be influential globally, it is increasingly held back by internal structural limitations. Ultimately, addressing these issues will be critical for the Party because significant economic downturn might break the social contract between the Party and the Chinese people, making it a survival issue for the Party.