China’s Investments in the Post-Coup Myanmar: An Assessment

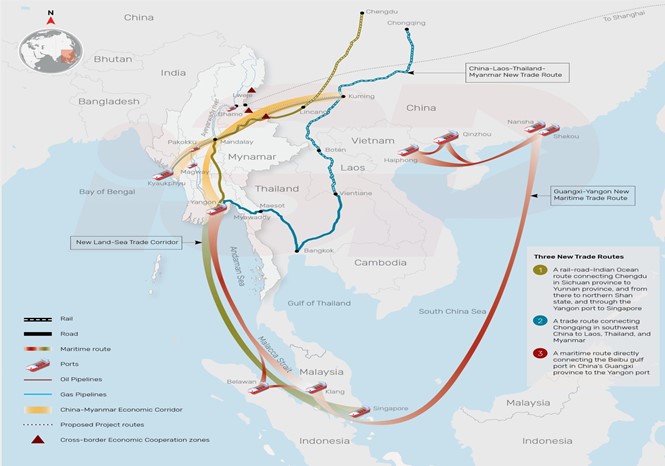

The relations between Myanmar and China have improved since the coup in February 2021. Both the countries are optimistic about three recent new projects to benefit their economies. The rail-road-Indian Ocean Route connects Chengdu in Sichuan Province with Singapore through Yunnan Province, the Northern Shan State and finally with the Yangon port. The trade route connects Chongqing province in Southwest China with Myanmar including its neighbouring countries like Laos and Thailand. The maritime route connects directly the Beibu Gulf port in China’s Guangxi province with Myanmar’s Yangon port[i]. These connections will supplement projects like China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) or Lancang Mekong Cooperation (LMC) under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The three development projects (shown below in figure 1) will enhance Myanmar’s geopolitical significance for China.

Figure 1: China’s Three New Developments in Myanmar

Source: https://www.ispmyanmar.com/three-new-china-myanmar-cross-border-trade-routes/

Surprisingly, when most Asian countries including India, Japan and Singapore paused to provide their aids, and some countries even terminated their investment, and discontinued their operating business in Myanmar[ii], it was a huge leap for China to grasp the opportunity. Thus, China continued its investment for new developmental projects, and took suitable steps for the completion of those pending projects. Currently, China stands Myanmar’s largest supplier of foreign investment after Singapore and the largest trade partner[iii]. The total budget of Chinese investment in Myanmar from 1988 to June 2019 is more than USD 25 billion[iv]. Besides, projects such as ‘China-Myanmar Ayeyarwaddy River Economic Initiative’ or ‘China-Myanmar Silk Road’ are in the pipeline to encourage Chinese goods to its neighbouring countries.

Prior to February 2021, China could not complete its infrastructural development projects due to anti-Chinese public sentiment prevalent in various parts of Myanmar, and a number of protests surfaced under multiple actors[v] since China’s investments were mostly concentrated in the natural resource sectors that might affect Myanmar’s ecological biodiversity[vi]. However, China never stopped its attempts to improve its relations with Myanmar. A point in case is China’s stand on Rohingya issue. Besides, China along with Russia did not sign a UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) resolution regarding situation in Myanmar in the post-coup[vii]. Thus, building a cordial relation with Myanmar has benefited China’s interest in the region.

Today, China and Myanmar surpass the ‘pauk-phaw’ concept meaning ‘brotherhood’ to define their close association. Under the military junta, Chinese foreign investment in Myanmar is the main source of foreign investments in pursuance of its Two-Ocean strategy[viii]. Not only interested in Myanmar’s potential on energy, China wants to invest in building infrastructures in mining, hydropower, oil and natural gas[ix]. In addition, several projects such as gas-fired power plant costing $ 2.5 billion[x] in the West of Yangoon, which are 81% owned and operated by Chinese companies, projects on high speed road, rail links and dams to encompass oil and gas pipelines could be mentioned.

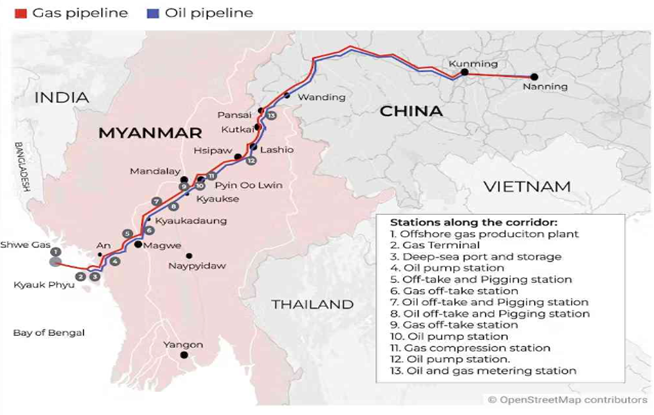

The project ‘Jewel in the Crown’, a deep-sea port built at Kyaukphyu on Myanmar’s West coast will facilitate China’s dream of ‘back door’ to the Indian Ocean, an easier way to import gas and oil from the West Asia, Africa and Venezuela without sailing through the contested waters of South China Sea to Chinese ports[xi] (shown in Figure 2). This project will alter China‘s traditional maritime trade routes with a new route without sailing through Malacca Strait. In addition, CMEC signed in 2017 is to connect China’s Yunnan province with the western flank of Bay of Bengal and southern part of Myanmar, Yangon via Mandalay in Central Myanmar. The main goal is to get direct access to seas, and improve its trade relations with South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Figure 2: China’s ‘back door’ in Indian Ocean

Source: https://scroll.in/article/1037882/china-is-pouring-money-into-junta-ruled-myanmar-to-secure-a-back-door-to-the-indian-ocean, (Photo credit: Vivekananda International Foundation)

China not only maintains a good rapport with Tatmadaw, it tries to improve its relation with conflict groups such as Ethnic Armed Organisation (EAO), non-state combatants by offering arms. Thus, China exploits every possible tactics to build trust with Tatmadaw and at the same time with opposing groups.

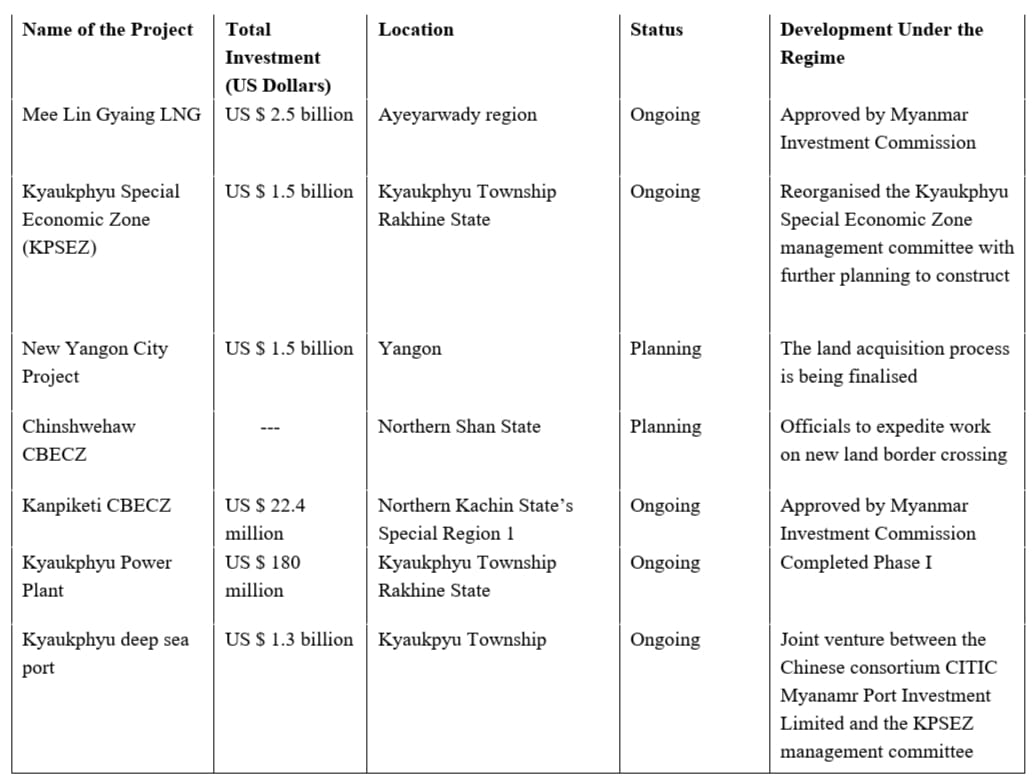

Table 1: China’s BRI Projects in Post-Coup Myanmar

Source: Sreeparna Banerjee and Tarushi Rajaura.2021. “Growing Chinese Investments in Myanmar post-coup”. Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

India-Myanmar Relation since February 2021

India being the largest democratic country in the world, always supported restoring democracy in Myanmar. It reacted vociferously against the 1962 & 1988 military coups in Myanmar. Nevertheless, India reorients its diplomatic endeavour with Tatmadaw since February 2021 and maintained a good rapport without compromising with Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD). India tried to keep its relationship with Tatmadaw by attending Annual Myanmar’s Armed Forces Day on 27 March 2021 with eight other countries[xii]. It was followed by the visits of the Foreign Secretaries in Myanmar, Harsh V. Shringla, in December 2021- discussing the ASEAN five-point consensus and the need for democracy to return to the country [xiii] and Vinay Mohan Kwatra in November 2022- discussing the border security, insurgency, trafficking concerns and review of bilateral developments projects[xiv] respectively. Besides the political front, India and Myanmar improved their bilateral trade by increasing their exports and imports (USD 892 M & 1002M) in 2021-22[xv] compared to 2020 (USD 871M & USD 742M)[xvi].

Assessment

China’s main interest in Myanmar is to get direct access to the Indian Ocean; amplify its regional interests both geopolitically and economically. Therefore, these new projects will strengthen China’s influence in the region. Once these projects fructify in Myanmar, the ripple effects would spread to other countries, who will welcome China’s investment.

Likewise, Myanmar is geo-strategically significant for India since it is located at the confluence of East Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia. Besides being India’s gateway to Southeast Asia, Myanmar is crucial for bolstering India’s Act East Policy since it shares land borders of 1,624 km long with India’s Northeast region (NER) and a maritime boundary of 725 km long in the Bay of Bengal. In addition, the country is critical to increasing India’s performance in regional diplomacy and contribution to the Indo-Pacific. Most importantly, both countries share cultural affinity- there is people-people connect for those living across the border.

Given the increasing China’s influence in Myanmar, India’s infrastructure developmental projects with Myanmar, such as India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highways, the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project (KMMTTP: an economic corridor which is in the pipeline to complete connecting North East Region and Myanmar); the Mandalay Bus Service and the Mekong-India Economic Corridor should be speeded up. New Delhi needs to adopt a proactive approach with the Tatmadaw as its strategic partner without losing hope of restoring democracy in Myanmar. Further, India and Tatmadaw must complete those pending projects; start new projects by exploiting the potential and reserved resources of the Northeast and making the region a vibrant market by boosting the economy, and encouraging border haats from both sides to promote small-scale businesses. Further, China’s close friendship with Myanmar is not a healthy sign for India. It might affect India’s eastern flank and the trade and market in South East Asia (SEA), resulting in a slowdown of India’s Act East Policy (AEP). Therefore, India needs to continue its relationship with Tatmadaw and other groups to the fullest to promote the interest of both countries without further delay.

Endnotes

[i] “China, Thailand and Singapore Remain Myanmar’s Top Trading Partners”. 2022. The Institute for Strategy and Policy (ISP)-Myanmar. December 19, 2022. https://www.ispmyanmar.com/china-thailand-and-singapore-remain-myanmars-top-trading-partners/ . Accessed on 20 February 2023

[ii] Sreeparna Banerjee and Tarushi Rajaura. 2021. “Growing Chinese Investments in Myanmar post-coup”. Observer Research Foundation (ORF). November 2021. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/growing-chinese-investments-in-myanmar-post-coup/. Accessed on 20 February 2023

[iii] Sreeparna Banerjee and Pratnashree Basu. 2021. “India-Japan Partnership in Third Countries: A Study of Bangladesh and Myanmar”. Observer Research Foundation (ORF). 460. Available at

https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ORF_IssueBrief_460_India-Japan-Bangladesh-Myanmar.pdf. Accessed on 27 February 2023

[iv] Ibid

[v] Yuka Kobayashi and Josephine King. 2022. “Myanmar’s Strategy in the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor: a failure in hedging?”. International Affairs 98(3).. https://academic.oup.com/ia/article/98/3/1013/6564934. Accessed on 5 March 2023

[vi] “Commerce and Conflict: Navigating Myanmar’s China relationship”. International Crisis Group (ICG), Asia Briefing no. 305. 30 March 2020. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/305-commerce-andconflict-navigating-myanmars-china-relationship. Accessed on 1 February 2023

[vii] Sreeparna Banerjee and Tarushi Rajaura. 2021. “Growing Chinese Investments in Myanmar post-coup”. Observer Research Foundation (ORF). November 2021. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/growing-chinese-investments-in-myanmar-post-coup/. Accessed on 20 February 2023

[viii] David Scott. 2017. “Chinese Maritime Strategy for the Indian Ocean”. Centre for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC). 28 November 2017. https://cimsec.org/chinese-maritime-strategy-indian-ocean/ . Accessed on 10 March 2023

[ix] Htwe Htwe Thien. 2022. “China is pouring money into junta-ruled Myanmar to secure a ‘back door’ to the Indiana Ocean”. Nov 22, 2022. https://scroll.in/article/1037882/china-is-pouring-money-into-junta-ruled-myanmar-to-secure-a-back-door-to-the-indian-ocean. Accessed on 15 March 2023

[x] “Junta approves $ 2.5 bn power plant project backed by Chinese companies”. Myanmar Now. May 14, 2021. https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/junta-approves-25bn-power-plant-project-backed-by-chinese-companies. Accessed on 3 March 2023

[xi] Htwe Htwe Thien. 2022. “China is pouring money into junta-ruled Myanmar to secure a ‘back door’ to the Indiana Ocean”. Nov 22, 2022. https://scroll.in/article/1037882/china-is-pouring-money-into-junta-ruled-myanmar-to-secure-a-back-door-to-the-indian-ocean. Accessed on 15 March 2023

[xii] “India attends military parade in Myanmar in Myanmar 2 months after coup. Why it’s significant”. India Today. March 30, 2021. https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/india-attends-military-parade-myanmar-months-after-coup-why-significant-1785075-2021-03-30. Accessed on 27 March 2023

[xiii]https://mea.gov.in/pressreleases.htm?dtl/34723/Visit+of+Foreign+Secretary+Shri+Harsh+Vardhan+Shringla+to+Myanmar+December+2223+2021. Accessed on 27 March 2023

[xiv]https://mea.gov.in/pressreleases.htm?dtl/35910/Visit_of_Foreign_Secretary_to_Myanmar_November_2021_2022. Accessed on 27 March 2023

[xv] “India-Myanmar Business Meet”. September 20, 2022. Virtual Platform. https://www.ciihive.in/Aboutus.aspx?EventId=INDMYAN22#:~:text=India%20has%20been%20a%20major,of%20around%20US%241002%20million. Accessed on 27 March 2023

[xvi] “The Observatory Economic Complexity (OEC)”. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/ind/partner/mmr. Accessed on 27 March 2023

434c4157532f57412d3030342f323032332f30342f3038