Abstract:

China views the current global security order as flawed and strives to establish an alternative security architecture while ensuring its rise and safeguarding its rights. However, China’s role concerning unresolved geopolitical tensions and a lack of strategic trust remains unanswered. The potential impact of the Global Security Initiative (GSI) on the strategic outlook of China’s adversaries cannot be overlooked. It is imperative to make adequate preparations and respond appropriately to avoid being caught off guard, as has been the case with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This commentary delves into the reasons why China has proposed the GSI now, the underlying motivations for renewing its bilateral and multilateral security diplomacy, and the institutions and content involved.

Keywords: Global Security Initiative, China’s Security, Chinese Foreign Policy, China’s Diplomacy

China’s new Foreign Minister Qin Gang presented the Global Security Initiative (GSI) Concept Paper while delivering a keynote address at the Lanting Forum in Beijing on 21st February 2023[i]. This marked the first official document detailing China’s plans concerning global security since President Xi Jinping first proposed the GSI with little detail in April 2022. As is customary, extensive internal debates have developed both affirmative and negative arguments on China’s determination[ii]. Some have also assessed the effects of the GSI’s “notional and somewhat vague” vision on global security politics[iii]. Whether the GSI undermines US alliances or just aims at China’s quest for global influence and securing its role in an emerging security architecture needs to be assessed.

The GSI’s vision of “uphold[ing] the vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security, pursues the long-term objective of building a security community”[iv] has generated debates over how policy changes will affect the current status quo and existential, structural, and attitudinal inherency. Critics question whether GSI is a response to the Indo-Pacific strategic focus or signals something more significant.

The objective of China is to offer and establish a “new” and “alternative” global security architecture using GSI against the “Western-led-global security order”. Indeed, China sees the current security order as “an era rife with challenges” and an opportunity to shape it to its advantage. GSI’s agenda includes mediating conflicts, (re)building China’s international image and attracting security partners, safeguarding overseas assets, and driving global security order. These aspirations demonstrate how China intends to use GSI diplomacy to shape security architecture in the coming decade. Moreover, China also presented GSI in a way that Beijing looks open and flexible, subjected to offer revisions based on how the international community responds to it.

GSI is likely to bring policy changes that require extensive research. Although GSI may appear targeted at Asia regional security, China’s focus is actually at the global level. In the early stage, the GSI was a supplementary policy of the Global Development Initiative (GDI). Surprisingly, BRI has no mention in GSI; indicating that China’s external economic initiatives are now part of GDI. The new Global Civilizational Initiative (GCI) is a political counterpart that aims to foster coordination and dialogue with political parties around the world. The reason behind separating GSI from GDI is to address China’s security concerns, and this move is expected to help manage regional tensions and political demonstrations against Chinese overseas investments in each region. It is noteworthy that each regional security dialogue initiated by China is now under the GSI’s umbrella.

Why GSI Now: Countering US Influence or Creating an “Asia-Pacific Security System”?

China’s increasing economic and geopolitical influence globally has made it more vulnerable to security threats, which is why China has turned to GSI. This initiative allows China to gain support from several countries in the ‘Asia-Pacific’ region to address security challenges, assert its influence and protect its interests; GSI is very much part of China’s desire to counter the influence of the US and its allies.

First, Xi Jinping’s recent re-election has sparked interest in domestic and external audiences about the ‘unprecedented’ third term, continuity, and potential changes (if any) in existing policies. Xi sees himself as a global leader and intends to aggressively pursue China’s “rightful position” with proposals that have the potential to change the status quo. In particular, internal Chinese debates are useful; which call for a separation between Xi’s Era from 2012-2020 with Xi’s “New Era” from 2022- 2032. Non-Chinese assessments suggest that China desires to improve its international image, which has suffered since the outbreak of the Covid-19 Pandemic. It is evident that GDI, GSI, and GCI are part of China’s efforts to (re)build its image and project the country as a responsible global player.

Second, China believes Foreign Minister Qin warrants global attention when he goes to conduct negotiations at high-level meetings. Qin has stressed the importance of “implementing GSI at every level” internally through state institutions and externally with “all countries and people”, including non-governmental organisations. Qin has also personally taken on the responsibility of overseeing the underlined implementation of GSI.

Third, there are disagreements between China and others on how to address traditional and non-traditional security threats and challenges of emerging new domains. In the face of intensifying US-China strategic competition, China opened debate on GSI as an extension of the national security concept, aligned with Xi Jinping’s other concepts, including the “New Security Concept”, “Major Power Diplomacy”, “Asian for Asian” and ‘Asia-Pacific Security System’.

What’s On GSI Agenda?

One aspect which deserves more attention is China advocating the principle of “indivisible security” as a global norm. This term, which derived from “Russia’s ire against NATO”,[v] suggests that the security of one country in a region is inseparable from that of others. With the proliferation of Indo-Pacific security consultations such as QUAD, AUKUS and I2U2, China seeks to build a narrative that these are not only at the expense of its security and also have “a negative impact on peace and stability”[vi]. By evoking collective security in its insecurity, Beijing is conveying a message that it now regards its national security as inseparable from global events[vii].

China’s GSI considers all types of security threats and challenges as part of “indivisible” security and encourages the participation of “all countries” in its “pilot projects” in each region, as emphasised in its six “Core concepts and principles”, twenty “Priorities of cooperation”, and five “Platforms and mechanisms”. However, the Concept Paper has a different tone, emphasising Beijing’s “ready[ness] to strengthen communication and garner exchange with the international community” while rejecting what it perceives as a “Cold War mentality”.

When a major power proposes concepts and principles in global security governance, conditioned with wider acceptance, they most likely become norms, rules, and regulations. China uses the collective security concept to influence debates that adhere to ‘universal security’ and ‘common security’. In recent times, a similar exercise has been aggressively pursued by proponent countries of the Indo-Pacific. The incorporation of globalist-sounding notions in the Paper reflects China’s intentions and adaption to changing times. At the same time, the Indo-Pacific vision includes terms like “free and open, connected, prosperous, secure, and resilient”; each of these terms has been separately referenced in the GSI. However, it is important to note that the context and interpretations of these terms in the GSI may differ from those in the Indo-Pacific vision.

GSI’s Priorities

Upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that the last sentence of each “Priorities” in the GSI clearly indicates that its ultimate goal is to address the underlying causes of global conflicts. These priorities are not merely a list; rather, they are a set of directives.

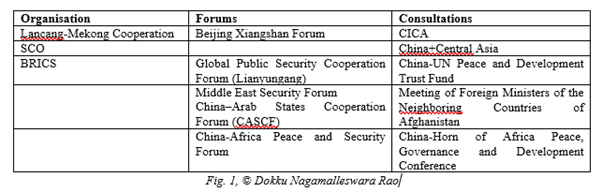

Anticipating potential opposition from other major players in the security arena, China has tasked its Armed Forces, internal security agencies, the Party’s external wings, and the Foreign Ministry with implementing the Concept Paper as a guide for successfully carrying out GSI projects. Over the next five years, they have been assigned to engage in nearly 1,000 exchanges and establish international platforms and mechanisms, including 11 China-supported and non-western platforms. Figure 1 depicts China’s preferred platforms for promoting GSI.

The priorities behind China’s GSI can be categorised into four main factors.

First, China seeks to shape the world order according to the Communist Party’s revolutionary aspirations. The same posture is the essence of Xi Jinping’s vision of the “Chinese Dream” in the “New Era”. The GSI acknowledges the changing world order, which is “changing in ways like never before” and facing “multiple risks and challenges rarely seen before”. Therefore, it asserts that a “new” and “alternative” world order is required. This view was reflected in Xi Jinping’s statement to Russian President Putin:

“Right now, there are changes, the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years. And we are the ones driving these changes together”[VIII].

Second, the GSI aims to attract regional security partners by mediating conflicts. With the heightened US-China strategic rivalry, Beijing circles view this as the right time for a global campaign to attract potential security partners. A Global Times commentary explains with little ambiguity what “the China-proposed security vision clearly targets”, particularly the US-led bloc[IX]. Recent examples demonstrate this strategy, such as the Saudi-Iran Deal and the peace plan for the Russia-Ukraine Conflict.

Third, the GSI seeks to address security challenges to China’s overseas assets. China’s BRI projects have faced intense pressure from regional security hotspots, local conflicts, domestic turbulence, the Covid-19 Pandemic, and “unilateralism and protectionism”. As multilateral mechanisms have avoided actionable intervention in the Russia-Ukraine Conflict, China has become less confident and cautious about relying on them. Beijing worries that if a similar situation arises involving China, multilateral instruments might fail to protect its interest. It is, therefore, reasonable to attribute the development of the GSI to China’s rethinking of its approach to securing its overseas investments and its increasing willingness to pursue its own initiatives independently.

Fourth, the GSI sought to share the “global security architecture”. GSI asserts China’s confidence and comfort in bilateral and regional multilateral interactions to compete and counter the proliferation of minilateral initiatives. It is apparent in Qin’s speech that China takes regional threat assessment seriously and would likely address regional security challenges within the Chinese version of the ‘coalition of the willing’. Conversely, China is not opposed to using locally-led regional security platforms. The contradiction lies in China framing the GSI as “the common pursuit of all countries” while also expressing frustration over the formation of growing regional alliances. However, this may be perceived as China taking its security initiatives to the centre stage, potentially undermining major security players’ initiatives.

Overall, the GSI has significant implications for China’s role in global security governance, as well as its relationships with other major security players. By understanding the priorities behind the GSI, one can better comprehend China’s strategic priorities in the realm of international security.

GSI Diplomacy: Ensuring China’s Say in Global Security

The GSI Concept Paper is seen as a flyer for China’s diplomacy for Xi’s third term[x]. So far, the indications are that GSI will likely receive greater marketing and publicity than BRI. The release of concept notes is part of the regular exercise of familiarising China’s initiatives to ensure wider attention. Besides, the careful choice of place and timing also explain that China also focuses more on rebuilding its image as a “responsible country”.

Diplomacy Starts at Home – China’s choice of the place for the launch of GSI, at the Lanting Forum in Beijing and the first BRI Forum in Beijing (2017), is telling of its intentions. GSI was first proposed at the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2022 in Hainan Province.

China-Centred Regional Diplomacy – GSI was proposed during the first in-person foreign trip of Xi Jinping for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Similarly, the BRI was first (2013) announced in Central Asia (Astana).

China is confident about addressing security challenges with traditional measures in the eastward security outlook, such as disputes with Japan, Taiwan, and [including] India. However, on the West and extended periphery, it steps up coordination in non-traditional aspects, such as strengthening SCO in Central Asia and initiating new “Middle East” Security Dialogue.

Using GSI, Chinese diplomats aim to ensure China’s say in global security issues. Although the Concept Paper expands the scope of “Core National Interests”, it also compartmentalises security issues within it. It divides China’s efforts against security challenges into traditional, non-traditional, and new areas. Traditional areas focus on nuclear war, arms race, regional security hotspots, transboundary rivers, and outer space. Non-traditional areas deal with local conflicts, transnational crimes at sea, terrorism, water resources politics, food security, energy security, and biosecurity. The new areas are information security, cyber threats, artificial intelligence, and “Unilateralism and Protectionism” in emerging technologies. With the GSI, China tends to prefer hosting regional dialogues while also accepting invitations to participate as a guest in others led initiatives.

Diplomatic Rhetoric and Ambiguous Actions

In the GSI paper, China has expressed concerns regarding global and regional security issues, some of which have touched on the US-China strategic rivalry. China could aggressively advocate for new CBMs, dispute settlement dialogues and consultations which “prioritise” high-level “political solutions” and “settlements”. Such projects aim to secure major space for China in evolving global security architecture. While Xi’s China proposes that countries adapt to the changing international landscape in the spirit of solidarity, it is unclear if this means taking China’s side.

It is expected that China’s diplomatic statements and comments continue to cite the need to respect “sovereignty and dignity”, “no external interference”, and the “right to independently choose social systems and development paths” while also criticising the “Cold War mentality, unilateralism, bloc confrontation and hegemonism”. Nevertheless, there is a gap between how much China honours and commits to the same in the region, which is ambiguous when it has active disputes.

Although China recognises the importance of “strategic communication,” its efforts to engage or respond so far have been weak. Additionally, China’s lack of confidence is evident in its loose approach towards the Korean Peninsula and the South China Sea. It is unclear, with no mention of the “Asia-Pacific,” “Indo-Pacific,” or the “Russia-India-China (RIC)” trilateral framework in the GSI concept paper raises questions about whether China prefers ambiguity in its approach.

China’s major focus is on the UN mandate, resolutions, and mechanisms, with a vested interest in shaping the UN mandate and regional agenda overseas. By committing to “abiding by the purposes and principles of the UN Charter”, China is open to using the existing institutional design. However, many are dissatisfied with the UN’s ineffective maintenance and implementation of its collective security and lasting peace mandate, which presents an opportunity for China to push its GSI model. China plans to engage actively and fund selected projects through the China-UN Peace and Development Trust Fund, mobilising global resources for major global infectious diseases, safeguarding the international drug control system, maintaining stable and smooth supply and industrial chains, and taking action for climate resilience.

Summary:

China’s GSI’s primary goal is to create a “peaceful and stable external environment” to facilitate its rise and ensure its “rights fully guaranteed”. With the changes in global security politics and reorienting regional alliances, China has taken a confident posture in releasing the Concept Paper, which marks the initiative’s official launch. In the coming months, China is expected to follow up with an annual summit and comprehensive doctrine or White Paper.

As most were not prepared adequately for BRI projects, consequences left many countries in somewhat of a predicament; thus, counter efforts to BRI have failed to accomplish any outstanding strategic gains – instead and Indo-Pacific-centered strategies and initiatives have been limited in their response.

China’s rise has been a common denominator in various initiatives, including Japan, India’s Asia Growth Corridor, and SAGAR; Australia’s Indo-Pacific Endeavour 2022; the US’ Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF); South Korea’s New Southern Policy; Taiwan’s New Southbound Policy; and QUAD. Efforts countering China’s BRI have been pushed to the margins due to a lack of financial and policy backing.

The timing of the Concept Paper’s release on the anniversary of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict and its content deeply reflects China’s bid for the “rightful place” in global security architecture[11]. China intends to forge security cooperation within the framework of bilateral, regional, and global organisations under the GSI and aims to use UN resolutions and mechanisms to promote the initiative. In the process, Chinese diplomats will now actively promote their security concepts and seek coordination in alignment with its security interests.

The desire to project China as a responsible global player brings in changes in its foreign policy priorities. As China continues to rise, serious work needs to be done on its strategic communication. If China intends to deflect the current geostrategic focus in its neighbourhood, it needs to come up with a better version of a Concept Paper whose past initiatives were acknowledged by many, adapted by few and contested by some.

[1]*Government of PRC (2023), The Global Security Initiative Concept Paper, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/202302/t20230221_11028348.html, Accessed on 21 February 2023.

[2]CGTN (2022), “President Xi proposes Global Security Initiative”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JUXxN0lzT10, Accessed on 21 February 2023.

[3]CSIS (2022), “Xi’s New Global Security Initiative”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QymyvJ_wmbw, Accessed on 14 March 2023.

[4] No.1

[5]Polina Ivanova and John Paul Rathbone (2022), “What is ‘indivisible security’? The principle at the heart of Russia’s ire against Nato”, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/84a43896-2dfd-4be4-8d2a-c68a5a68547a, Accessed on 26 February 2023.

[6]*Government of PRC (2023), Joint Statement between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation on Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination in the New Era, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/zyxw/202303/t20230322_11046188.shtml, Accessed on 22 March 2023.

[7]Brig. Anil Jain (2022), “China’s Global Security Initiative: A Preliminary Assessment”, MANEKSHAW PAPER No. 97, Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi.

[8]*Xi Jinping (2023), China’s Xi tells Putin of ‘changes not seen for 100 years’, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/22/xi-tells-putin-of-changes-not-seen-for-100, Accessed on 02 April 2023.

[9]Chen Qingqing and Bai Yunyi (2023), “China issues Global Security Initiative (GSI) Concept Paper, calling to resolve disputes through dialogue and rejecting power politics”, Global Times, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202302/1285892.shtml, Accessed on 02 April 2023.

[10]CGTN (2023), “Diplomats voice support for China’s Global Security Initiative proposal”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YfhIKFDbSlA, Accessed on 22 March 2023.

[11]CGTN (2023), “How can China’s global security initiative help in the Ukraine crisis?”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgY5XH_cWMk, Accessed on 25 February 2023.

434c4157532f57412d3030352f323032332f30342f3130